Dear Sir,

I am writing to complain about a joke that was made in the I’m Sorry I Haven’t a Clue broadcast on Saturday 27 December, near the beginning, between 1’33 and 1’48” on the iPlayer recording. Part of Jack Dee’s introduction, this attack on ‘cyclists’, implying they do not know the Highway Code, was offensive, cheap and unpleasant humour to me, and to many others who I know.

I am sure you will claim that Clue is an ‘irreverent’ programme where attacks or jibes are meted out without fear or favour to all sorts of groups. Yes, the jokes following this ‘got at’ steam railway enthusiasts and UKIP supporters. But the joke against cyclists was unpleasant in a way that these, and similar jokes in the show, are not. They do not have the hostile majority-minority power-play implied that the joke against ‘cyclists’ did.

The background to this is that around 120 cyclists are killed on the roads of the UK every year and about 3,000 seriously injured (a figure that has been increasing in recent years). This is a bad record by international standards – cycling on the UK's roads is at least twice as dangerous as in some neighbouring European countries. According to statistics of police analysis of these incidents, in most cases the killed or seriously injured cyclist was not at fault and was cycling correctly and legally, and therefore most of these cyclist deaths and injuries are due to bad, illegal, and dangerous driving: that is, drivers wantonly ignoring the Highway Code. Yes, there are infringements of the Highway Code by all user-groups, but motorists have far more power to do damage than cyclists, who will in general only put themselves at risk by behaving badly on the roads. The issue is therefore the dangerous and irresponsible behaviour by those in control of powerful motor vehicles.

Unfortunately our society normalises many aspects of this behaviour, particularly the crime of speeding, and there is a mentality amongst many motorists that they have superior rights to the road compared to non-motorised users, and a culture of victimising cyclists with socially-widespread and acceptable inaccurate, prejudiced claims about their behaviour. It is right into this trap that the Clue joke about the Highway Code fell.

This kind of humour would be totally unacceptable when applied against religious or racial minorities, or other groups, such as the disabled. Cyclists have to put up with it as normality. It helps to sustain a set of attitudes in the public and official bodies that result in cases, such as the recent one of Michael Mason, a cyclist killed by a motorist on Regent Street (very close to Broadcasting house) where the driver who killed him has received absolutely no punishment despite effectively admitting full guilt and responsibility. The mythology of blaming and victimisation of cyclists excuses these deaths to our society and makes acceptable the fact that no-one is held responsible for road deaths in cases such as these, or if they are, they typically receive derisory punishment.

I expect many BBC employees cycle to work on Portland Place and Regent Street, where Michael Mason, an experienced and expert cyclist, was killed, through no fault of his own. I wonder if any cycling BBC employees had the ‘Highway Code’ joke run past them before it was broadcast. I expect the answer is no, as if it had been, the scriptwriters would have realised their error. This was an offensive joke and should not have been broadcast. This was a favourite Radio 4 programme of mine, but I expect I will not be able to enjoy it in the same way again.

I hope these thoughts have explained to you why the BBC should apologise to the cycling community, and cycling organisations, for this error of judgement.

Yours,

David Arditti

Mostly about cycling in the

"Biking Borough"of Brent

and elsewhere in London,

but also touching on

environment, politics,

philosophy, science,

society, music and art

Wednesday, 31 December 2014

Friday, 5 December 2014

Whatever happened to the Biking Borough money?

After Boris Johnson won the 2008 London mayoral election, he formulated a new cycling strategy which involved ditching Ken Livingstone's London Cycle Network Plus programme, which had run into the sand because of a lack of political will to tackle the main barriers to cycling in London like dangerous junctions, and was never predicated on high-quality infrastructure standards anyway, and replacing it with a combination of the first-generation Cycle Superhighway plans, to affect mainly Inner London, and a project called Biking Boroughs, which was for Outer London.

The initial Cycle superhighways (sponsored by Barclays) were merely strips of blue without any legal backing, mostly painted inside bus lanes on main roads, and often disappearing altogether where there were competing demands for road space. They did not treat major junctions in any safe or logical way, leaving them much as they had been, the blue lanes sometimes disappearing from an inside lane and reappearing in an outside one, leaving hapless cyclists to cut across multiple lanes of fast-moving motor traffic, if they dared. They were of course massively criticised, and at the time I commented, to the London Cycling Campaign:

But let's go back to that other, less-publicised strand of Boris's first cycling strategy, the Biking Boroughs. This seemed to come out of an idea, propounded by Transport for London in its Analysis of Cycling Potential report of 2010 that:

I can, however, report on what happened in one borough that was awarded Biking Borough cash: Brent.

Brent was awarded £294,500 of Biking borough funding to be spent in 2011/12, 2012/13 and 2013/14. This was one of the largest awards to any borough. This followed the production of a TfL-funded report for the council on the state of cycling in the borough. Anybody could have told them for free that the state of cycling in the borough was 'dire' or 'virtually non-existent', but this is not how local government works. Every time there is a new project, and any funding to do anything at all, first of all, a large tranche of that funding has to be spent on a report from external consultants that tells you what everyone can see anyway.

The Brent Biking Borough report can be found on the Brent Cyclists website. I am not sure how much this cost to produce, but funding was provided by TfL of 'up to £25,000' for such a study, so it's a fair guess that the cost approached this. I first came across the wonderful world of cycling blogs, literally, when someone pointed me to Freewheeler's devastating critique of the Brent Biking Borough report, amongst the highlights of which were these paragraphs:

The report was launched at a 'Stakeholder Engagement Forum' on 3 March 2010 that I attended. I described this event in the April 2010 Brent and Harrow Cyclists Newsletter:

Tiny and profoundly unambitious, or 'realistic', if you will, as these schemes were, none of them were realised. The reasons are too tedious to go into at length.

I mentioned Number 1 in a previous post, The red tape that strangles cycling provision. The red tape strangled this tiny proposed change. Though the bit of digging and kerbstone-lying required would only have taken a couple of men half a day to do, it would, apparently, have been too expensive to change the traffic order. (Some of the professional opinions on that latter post were that it should not have been, and that Brent officers were interpreting procedure or the law wrongly, but I cannot adjudicate on that. I can just tell you it did not happen.)

Scheme number two produced another set of meetings and a consultant's report, which proposed a bad fudge that no-one liked, and again that scheme never made progress. The consultant's suggestion of widening the barrier to create a cycling refuge in the middle of Brondesbury Park would just have created more problems for cyclists on that road. The solution for that location was clearly, and still is, clearly, for the barrier in the middle of the main road to be moved to one of the side roads, and for a cycle gap to be made into it there, with maybe a combined cycle-pedestrian crossing of Brondesbury Park to aid cyclists in getting across from one side road to the other. But that would be a change to the traffic system, with changes to allowed movements in and out of the side roads. Though this change would not necessarily be 'anti-car', car movements here are restricted by the current setup, Brent officers believed they would not win any consultation of residents in the area on such a change, which they believed firmly could be painted as being 'anti-car'. So nothing has happened, despite children and staff at Malorees Primary School in Christchurch Avenue, a school which is doing its bit to encourage cycling, wanting a route across here. This should have been a classic 'easy win' for cycling, but it couldn't be achieved in the three years of Bikling borough funding, though it remains on the Brent Cyclists Space for Cycling 'Ward Asks' wish-list.

The £294,500 awarded to Brent disappeared into promotional activities (such as dubious victim-blaming things like "Exchanging Places"), some funding for training courses and Sky Rides, and production of a promotional booklet about cycling in Brent, which contained basic errors, like a map that showed a route that did not physically exist, and promoted the dubious ideas that cyclists were safest using cycle infrastructure where available and that they should always wear a helmet.

I can't say anything about the Biking Borough projects in the other twelve boroughs. But the way the Biking borough played out in Brent was a scandal. The £300,000 went down the drain, emptied into the pockets of consultants and the people who made the blue signs, so purposeless in the absence of meaningful subjectively-safe routes on the roads they signposted. Only the few thousands of pounds spent on the cycle stands could be said to have been possibly money well-spent.

The £300,000 went down the drain because it was 'calamitously inadequate' to the task in hand, and nothing it could have been spent on would have caused substantial progress in raising Brent's cycling level from the existing 1% modal share to the Mayor's target of 5%. But it had to be spent, so it had to be wasted. After the money for the studies, money for leaflets, money to pay the lorries to come and do 'Exchanging Places', money for the events organisation and for the trainers was taken out, there was too little left, divided three ways between three tiny infrastructure schemes in a small (and anyway already relatively cycle-friendly) area of the borough, far from the disastrous cycling environment of the North Circular and the suburbs beyond, to even achieve those tiny schemes, given councillor-level indifference and officer-level timidity.

The Biking Borough project left Brent exactly as it had been before for cycling. Because it was such a small amount of money, I suppose no-one really cared about it. Boris's second term cycling strategy looks far better, because Andrew Gilligan has removed much of the fluff around 'cycle hubs' , 'cycling communities' and 'raising the profile', and directed a much larger investment into much clearer infrastructure objectives.

The three Outer London mini-Holland schemes in Walthamstow, Enfield and Kingston are each getting about a hundred times the Brent Biking Borough allocation. This is enough to matter, enough to make a difference, if spent wisely, and enough for people to care about getting wasted. On the other hand, some of the issues that bedevilled Brent's biking borough could come back to haunt the current mini-Holland and Quietway projects, and they should not be neglected. The Brent failure needs to be learned from, and I await this promised report into the overall effectiveness of the Biking Boroughs with much interest. Even if a sensible amount of money is provided to change an area of car-dominated Outer London, and even if it is not, this time, divided up into such small parts that nothing useful can actually be done with it, the same risks exist, of council double-speak, consultant opportunism, lack of engineering and administrative competence, timidity and foot-dragging, to waste it all again.

Four years after the Biking Borough study, and two years after its mini-Holland bid failed, Brent is conducting a survey to inform a new cycling strategy. There appears to be no limit to the amount of paper that can be pushed before we get the real infrastructural change in Brent that everyone interested in the subject can see we need. Since the end of Ken Livingstone's LCN+ project in 2008, not a single, tiny piece of cycling infrastructure has been built in the Biking Borough of Brent.

The funding and the conception behind these routes is so calamitously inadequate to the task that they will be a total waste of time and money, and, worse, will attract inexperienced cyclists onto main road routes that have not been made any safer than they are now, with junctions that are still highly dangerous and unsuitable for all but the most skilled with-traffic cyclists.Later came the much-publicised deaths on the 'calamitously inadequate' Cycle Superhighway 2, and following LCC's Go Dutch campaign and the appointment of Andrew Gilligan as Cycling Commissioner, we have a programme to rebuild the Superhighways to proper standards (or at least much better).

But let's go back to that other, less-publicised strand of Boris's first cycling strategy, the Biking Boroughs. This seemed to come out of an idea, propounded by Transport for London in its Analysis of Cycling Potential report of 2010 that:

The greatest unmet potential for growth can be found within outer London – 54 per cent of potentially cyclable trips – and only 5 per cent of the "total potential‟ in outer London is actually cycled, compared to 14 per cent of that for central London... and 9 per cent for inner London. The "total potential‟ is defined as the total number of trips currently cycled added to the number of potentially cyclable trips.

This was without doubt a true statement, given that so much of London's population lives and moves in the outer Boroughs, and given that cycling is so low there now, and yet one that gets us no further towards achievement of that potential without any definition of the standards that should pertain in the Outer London cycling environment, which were not hinted at by this study. Vagueness was thus built into the Biking Borough concept from the beginning.

The Biking Borough policy itself was very short-funded and gave little clue as to what it was actually trying to do in practice. I thought TfL might have tried to bury this embarrassment by now, but, surprisingly, a page on it still exists on the TfL website, saying this:

The Biking Borough policy itself was very short-funded and gave little clue as to what it was actually trying to do in practice. I thought TfL might have tried to bury this embarrassment by now, but, surprisingly, a page on it still exists on the TfL website, saying this:

Thirteen outer London boroughs were given a share of £4m funding over three years to help raise the profile of cycling, improve facilities and highlight safety awareness locally.

All of these Biking Boroughs are funding initiatives to encourage more people to take up cycling, whether to work, or in their leisure time. The activities involved include:

- Creating and improving cycle routes and access

- Educating people about cycle safely

- Making train stations more cycle friendly

- Building more cycle hubs

So a 'Borough' is an 'initiative': more confusion of thought and language. And to me, the term 'Biking' always suggested something to do with motorbikes. The first item, 'creating and improving cycle routes and access' sounds useful, but no-one actually could ever explain what a 'cycle hub' was, and Freewheeler's explanation is as good as any that I came across:

The answer is simple. A ‘bike hub’ is usually a shopping centre full of cars which contains no cycle parking. To access the ‘bike hub’ simply get on your bicycle and follow the signs that read ‘CAR PARK THIS WAY – PARKING FOR 600 CARS’. Remember to watch out for drivers of lorries, vans, 4X4s, Audis and BMWs, as these drivers find it particularly difficult to see cyclists.But seriously, I am interested to learn from the TfL webpage linked above that:

If your local council is ‘Green’ you might find some cycle stands tucked away around the back of the car park block. These are rarely signed but it is always well worth looking for the waste containers. Remember that most bike stands are traditionally located in close proximity to rubbish.

A full report on all Biking Boroughs will be published in 2014 including results, case studies and lessons learned.We are now almost at the end of 2014, and I have seen no sign of this report. It should be interesting.

I can, however, report on what happened in one borough that was awarded Biking Borough cash: Brent.

Brent was awarded £294,500 of Biking borough funding to be spent in 2011/12, 2012/13 and 2013/14. This was one of the largest awards to any borough. This followed the production of a TfL-funded report for the council on the state of cycling in the borough. Anybody could have told them for free that the state of cycling in the borough was 'dire' or 'virtually non-existent', but this is not how local government works. Every time there is a new project, and any funding to do anything at all, first of all, a large tranche of that funding has to be spent on a report from external consultants that tells you what everyone can see anyway.

The Brent Biking Borough report can be found on the Brent Cyclists website. I am not sure how much this cost to produce, but funding was provided by TfL of 'up to £25,000' for such a study, so it's a fair guess that the cost approached this. I first came across the wonderful world of cycling blogs, literally, when someone pointed me to Freewheeler's devastating critique of the Brent Biking Borough report, amongst the highlights of which were these paragraphs:

This MVA Consultancy report does a professional job of identifying the poor condition of cycling in Brent. However, it doesn’t diagnose it because it is incapable of understanding the reasons for it, and therefore its cures for the condition are rather like medical cures of the pre-modern era – a mixture of quackery and superstition. All the traditional cycling folk remedies are here – cycle training, signposting, promotional activities, recycling old bikes – and none of them will save the patient......

This report shows no understanding of the central importance of addressing subjective safety. Instead of safe and convenient cycling infrastructure what is really on the cards is developing relationships with parents to ‘encourage’ them to send their children to school on bicycles.

It won’t work. Cycling will at present only increase to the extent that people can be persuaded to cycle in Outer London traffic. There are few signs that persuasion and minimalist new cycling infrastructure will ever be enough to encourage the surge in cycling which even the Mayor’s deeply unambitious target requires. Cycling in Brent appears every bit as doomed to stagnate as it does in the London Borough of Waltham Forest or in any other Outer London borough.

The report was launched at a 'Stakeholder Engagement Forum' on 3 March 2010 that I attended. I described this event in the April 2010 Brent and Harrow Cyclists Newsletter:

The money that Brent was allocated by TfL under the Biking Borough project was divided up as follows:

We heard a lot of interesting statistics collected by the consultants, though the gist of most of the important ones are things we already knew or could pretty much have guessed. Facts included here were that the proportion of people cycling to work varies from 0% in much of the north of the borough to over 6% in Kensal Rise, that 90% of Asian residents never cycle, compared with 74% of white residents, and that the highest levels of cycling are amongst middle-income earners. This last came as a surprise to the consultants, but not to us...

The stated objective for the “Biking Borough” is to achieve a 5% modal share of trips by bike (TfL’s statistics say that the modal share is currently 1%). The main problem with this forum, in our view, was a general underplaying, or a lack of understanding, of the role of the physical environment in determining cycling levels. There seemed to be a naive view amongst some, including the consultants, that raising the levels of cycling in Brent would primarily be a matter of promotion or publicity. A concept of a “Cycle Hub” was being discussed, but it was entirely unclear what this was supposed to be. Boris has apparently introduced this concept, but not defined it, and it is up to boroughs to interpret. It seems, however, as if it is not going to be primarily conceived as the provision of physical infrastructure.

Participants were asked if they thought the strategy should focus on trying to get more cycling from communities in Brent that already cycle quite a bit, or on trying to reach the communities that are highly reluctant to cycle, such as the Asians of north Brent. We do not think that making any such choice is desirable. We believe that the cycling environment needs to be improved radically across the whole borough, and that doing this would, pretty much automatically, raise cycling levels in all communities. The measures that need to be taken are well-known, it is a matter of political will and the commitment of funding. The main points we were keen to emphasise were the widely- perceived danger of cycling on Brent’s roads, which will not go away with a bit of promotion, and the lack of cycle permeability of the borough, with the major barriers of the North Circular Road and the railway lines preventing the creation of attractive and safe cycle routes. Until the major funding needed to address these is forthcoming, we do not see much prospect of Brent really becoming a “Biking Borough".

Project area

|

TfL Biking Borough funding to your borough

|

||

2011/12

|

2012/13

|

2013/14

|

|

Cycle Hub

|

£54,500

|

£50,500

|

£50,500

|

Cycling Communities

|

£10,000

|

£10,000

|

£10,000

|

Raising the Profile

|

£6,000

|

£2,000

|

£2,000

|

Other

|

£33,000

|

£33,000

|

£33,000

|

Total per year

|

£103,500

|

£95,500

|

£95,500

|

What the headings on the left really meant always remained a mystery to me. But I can tell you that the 'cycle hub' selected was in the south of the borough, in Kensal Green. SKM consultants were engaged for three years to find ways of spending this money around this area (which was already pretty much the highest-cycling area of Brent, owing to it being fairly affluent and only three miles from the West End, and having no major main-road barriers worse than Maida Vale and the Harrow Road, and already a reasonable functioning twisty backstreet London Cycle Network route from the West End (via Hamilton Terrace, Blomfield Avenue and Shirland Road)). They thus thought that in a borough with generally exceptionally cycle-hostile infrastructure, this area would be the easiest nut to crack.

What the 'cycle hub' actually amounted to in the end was the installation of cycle stands, mostly at Kensal Green, Kensal Rise and Queens Park Stations, and other places on the streets, and provision of numerous blue direction signs around Kensal Green, giving cycling mileages to various destinations. The roads were not improved in any way at all, except that there was contemporaneously, and seemingly incidentally, not funded out of the Biking Borough budget, a programme of installing cycle-unfriendly speed cushions and speed tables on residential roads in the area. Cycling remained firmly banned in Queens Park, under the control of the Corporation of London, and so there remained pretty much zero traffic-free space for cycling in the area, and no-where to take kids to teach therm to cycle.

|

| Copious cycle signage supplied as part for the Biking borough Cycle Hub in Kensal Rise |

There was an attempt by the consultants and the council to identify some permeability measures that could be implemented on minor roads in the area. They whittled it down to three possible schemes:

- Tidying up of an exiting messy road-closure in Hazel Road, near Kensal Green Station, and formally allowing cycle passage through it;

- Removing or modifying the barrier in the centre of Brondesbury Park (a road) between the two halves of Christchurch Avenue (two side roads) to allow cycling between these two roads, currently blocked along with the passage of all other traffic in an existing anti-rat-running scheme;

- Allowing contraflow cycling on Clifford Gardens, just north of Kensal Rise Station.

|

| Possible scheme 1:Road closure in Hazel Road, bikes formally banned, no dropped kerb at far end |

|

Possible scheme 2: Christchurch Avenue barrier in Brondesbury Park: an easy-to-fix snag that eluded solution under the Biking Borough /Cycle Hub projects

|

|

| Possible scheme 3: Clifford Gardens |

Scheme 3, the contraflow on Clifford Gardens, a side-road off Chamberlayne Road, planned to connect with an existing contraflow (one of the few in Brent) on Bathurst Gardens, got further than all the others. Though there were doubts amonsts some cyclists as to how well this might work, with parking on both sides of this narrow road, and a need, if it the scheme were implemenred, for cyclists to face down some fast rat-running traffic in the confined space, it was supportyed by Brent Cyclists, as really the last hope of getting anything concrete out of the Biking Borough project, and it was designed and went to consultation. The results of the consultation were 52% in favour, 48% against. Brent Council decided that this was too close a margin, and abandoned the project.

It's worth reminding ourselves now that in 2011, in a letter to Brent's then Head of Transport, Ben Plowden of TfL wrote:

Your funding bid has now been evaluated against the following criteria:So even where a consultation was won, on the last-ditch attempt to push some change through using the Biking Borough cash, Brent Council turned back. So much for the 'local political commitment to increasing levels of cycling'. So much for the 'proposed changes'. So much for the 'step change in levels of cycling and good value for money'.

I am pleased to confirm that a total of £294,500 has been awarded to your borough to fund proposals relating to the development of Cycle Hubs, Cycling Communities and Raising the Profile of Cycling locally as set out in Table 1 below. I would like to congratulate you on the scope and quality of your bid.

- Demonstration of local political and stakeholder commitment to increasing levels of cycling;

- Evidence that the measures proposed will achieve a step change in levels of cycling and offer good value for money;

- Deliverability by March 2014.

The £294,500 awarded to Brent disappeared into promotional activities (such as dubious victim-blaming things like "Exchanging Places"), some funding for training courses and Sky Rides, and production of a promotional booklet about cycling in Brent, which contained basic errors, like a map that showed a route that did not physically exist, and promoted the dubious ideas that cyclists were safest using cycle infrastructure where available and that they should always wear a helmet.

I can't say anything about the Biking Borough projects in the other twelve boroughs. But the way the Biking borough played out in Brent was a scandal. The £300,000 went down the drain, emptied into the pockets of consultants and the people who made the blue signs, so purposeless in the absence of meaningful subjectively-safe routes on the roads they signposted. Only the few thousands of pounds spent on the cycle stands could be said to have been possibly money well-spent.

|

| A few stainless steel Sheffield racks are the only infrastructural legacy of the Brent Biking borough project |

The Biking Borough project left Brent exactly as it had been before for cycling. Because it was such a small amount of money, I suppose no-one really cared about it. Boris's second term cycling strategy looks far better, because Andrew Gilligan has removed much of the fluff around 'cycle hubs' , 'cycling communities' and 'raising the profile', and directed a much larger investment into much clearer infrastructure objectives.

The three Outer London mini-Holland schemes in Walthamstow, Enfield and Kingston are each getting about a hundred times the Brent Biking Borough allocation. This is enough to matter, enough to make a difference, if spent wisely, and enough for people to care about getting wasted. On the other hand, some of the issues that bedevilled Brent's biking borough could come back to haunt the current mini-Holland and Quietway projects, and they should not be neglected. The Brent failure needs to be learned from, and I await this promised report into the overall effectiveness of the Biking Boroughs with much interest. Even if a sensible amount of money is provided to change an area of car-dominated Outer London, and even if it is not, this time, divided up into such small parts that nothing useful can actually be done with it, the same risks exist, of council double-speak, consultant opportunism, lack of engineering and administrative competence, timidity and foot-dragging, to waste it all again.

Four years after the Biking Borough study, and two years after its mini-Holland bid failed, Brent is conducting a survey to inform a new cycling strategy. There appears to be no limit to the amount of paper that can be pushed before we get the real infrastructural change in Brent that everyone interested in the subject can see we need. Since the end of Ken Livingstone's LCN+ project in 2008, not a single, tiny piece of cycling infrastructure has been built in the Biking Borough of Brent.

Friday, 31 October 2014

The Mayor's Vision for Cycling in London: 18 month assessment

I last wrote extensively on The Mayor's Vision for Cycling in London shortly after it was announced, in March 2013. We are now 18 months on, so I thought I would try to assess 'how it is going'.

A reminder: the Vision is aiming for a doubling of cycling in London over 10 years, achieved mainly through these four programmes:

Now the first thing to say is that the rate of progress has been disappointing. Summer is the usual time for spades to be put in the ground for major work on the roads. I thought a year would be adequate for Transport for London to put their plans in place and assemble the correct staff, and that we would probably see something happening this summer. But summer passed, and nothing much happened, except a draft of the much-delayed, and in the event exceedingly lengthy and somewhat un-focused London Cycle Design Standards document was released for consultation. (See the excellent Cycling Embassy response on this.) The Cycling Commissioner, Andrew Gilligan, has been giving talks everywhere, and press releases have been common, but there's been no spades in the ground. What has been built in the last 18 months was either in train before (as was the Cycle Superhighway 2 extension), or the result purely of a borough initiative (as was the rebuild of the Royal College Street cycle track).

On the other hand, though it is getting going painfully slowly, there are signs of a seriousness to the project that go far beyond what we have been used to seeing before in the politics of UK cycle provision. I have, for example, actually watched (sad, benighted creature that I am) the examination of the chief officers of the project, including Gilligan and Lilli Matson, TfL's Head of Delivery Planning, by the GLA's Budget Monitoring Subcommittee. It is very clear if you watch this that we are in a rather different world to the borough Town Hall meetings of old where a 'Cycling Officer', a rather unimportant council employee who happened to be quite keen on cycling, would turn up before a few pretty uninterested councillors in a dirty yellow lycra suit and explain how he proposed to spend a few thousand pounds on painting some lines on pavements. Now, we have people establishing the serious business case for the expenditure, monitoring and auditing by actual outcome, of how many cycle journeys are generated, for hundreds of millions of pounds spent across a city of 10 million people. This is a hard-headed world which is little to do with wanting to 'look green' or create a bit of good PR with 'cyclists', but everything to do with keeping a major city moving and keeping it in business, and spending public money sensibly and effectively.

So what of the four programmes? In brief, if you haven't got time to read further, I'd say this: The Cycle Superhighways are now looking quite promising as the standards, programme and timetable for them is becoming clear. The timetable, nature and likely ultimate success of the Central London Grid is much less clear, and that is because TfL doesn't control most of it, the boroughs do. The programme for the Quietways is becoming slightly clearer, but the standard of implementation is in doubt. There seems to be a problem with people understanding the nature of the Quietways; Andrew Gilligan seems to have to keep explaining it again, and that must be his fault for not being clear enough from the start. The mini-Hollands still have not progressed sufficiently to draw any conclusions.

Superhighways

According to Gilligan at the budget subcommittee, around half of the total budget for Superhighways (£209m) is scheduled to have been spent by May 2016. The initial four superhighways that were created by painting the road blue – CS2 from Stratford to Aldgate, CS3 from Barking to Tower Gateway, CS7 from Merton to The City and CS8 from Wandsworth to Westminster are promised to be re-engineered 2016. However, the only one for which we have seen plans is the notorious CS2. These are being consulted on currently (ends 2 November), and look worth supporting, containing a large element of segregation, though the solution for Bow Roundabout is still sub-optimal, and a further round of improvements here is promised at a later date.

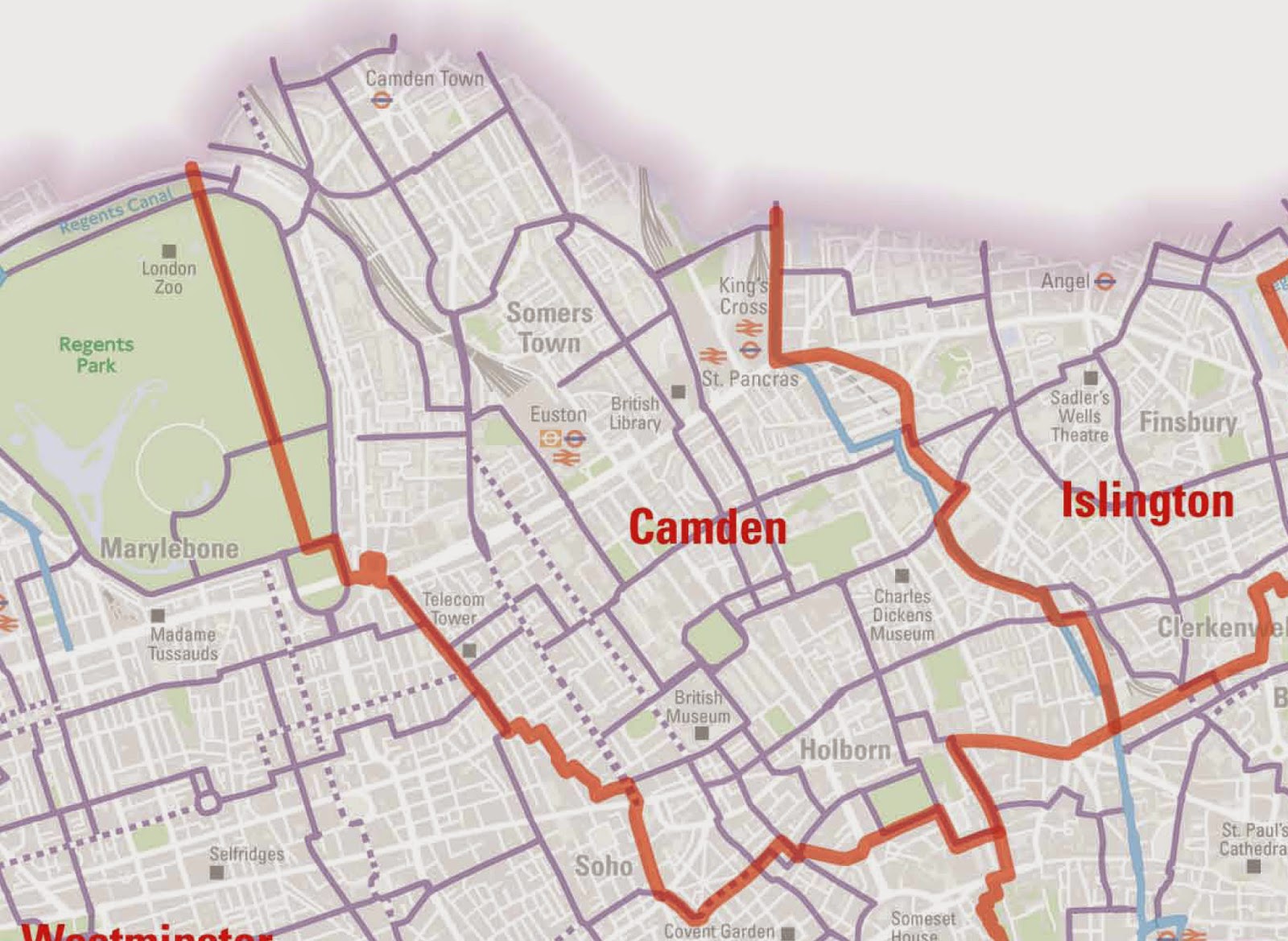

The plans for the East-West and North-south Superhighways are really not complete at all. The North-South, in particular, seem not to deserve its name, as it is just a 'stub' compared to the far more important East-West, and most of what has been planned is south of the Thames, further emphasising the Superhighway network's already very strong south-of-the-Thames bias. Far from getting anywhere near 'north' London, it peters out in the backstreets of Clerkenwell's existing Seven Stations Link (London Cycle Network Route 0) in the Ampton and Cubitt Streets area, seemingly baffled by the King's Cross Gyratory. It could connect with Camden's proposed route on Midland Road up towards Camden and Kentish Towns ultimately, but still it seems disappointing in concept compared to the East-West route: we might have expected a high-profile main road route up at least as far as Kings Cross. However, let's not be churlish: with a good segregated cycle track on Blackfriars Bridsge, we could finally declare the Battle for Blackfriars won.

There are still big gaps in the East-West plan, mostly concerned with the Royal Parks. What to do at St James's Park and in front of Buckingham Palace still has not been decided, though the suggestion of replacing the horse ride by Constitution Hill with a cycle track is a good one. Andy why, at the chaotic Wellington Arch, why do TfL propose 'a larger shared space to replace sections of grass to provide more space for pedestrians, cyclists and horses'? Why not just have clear dedicated routes so everybody knows where they are? Using the Carriage Drives in Hyde Park is a good plan, as they don't get disrupted by the park's frequent commercial entertainments, but these sections have not been designed yet. Different options are given in the Lancaster Gate area, and the idea for using the elevated A40 Westway to Acton seems still sketchy: further consultation on this is promised in 2015.

On the other hand, the plan for The Embankment, Bridge Street and Parliament Square is a clearly-defined game-changer: a high-capacity, high-profile two-way cycle track driven right past the Houses of Parliament and across the formerly intimidating and hostile gyratory of the Square. For this section alone the plans would deserve massive praise, and the scale and ambition of the East-West and North-South Superhighway concepts overall demand that all who are interested in the environment of the city and its transport network, whether they cycle or not, show their support.

That's a total of twelve Superhighways, the number originally projected, though they are not all in the originally projected locations. The original CS12 Angel to Muswell Hill and CS10 Hyde Park to Park Royal have been abandoned. CS10 is supposedly replaced by the East-West route on the A40, but this means, with the original CS11 alignment having been moved east, from the A5 to the A41, that Brent, quite an inner borough (though technically an Outer London one) will have been completely left out of the Superhighways programme.

I have to say I take all TfL's projected completion dates with a massive bag of salt. We were told, after all, in late 2012, that CS5, 9, 11 and 12 would be launched in 2013. Well, clearly the rethink on the whole nature of the CSHs after LCC's Go Dutch Campaign and the appointment of Gilligan as Commissioner caused that three-year delay. But the longer timescale is for the best if what we get is actually good. The designs we are seeing now show a step-change in quality from what we were offered before. Problems tend to come at a few places at big junctions where there is slightly too much emphasis on mixing and sharing with pedestrians: we need separation and clarity to allow flows of both cyclists and pedestrians to continue to grow and co-exist in harmony. We need efficient cycle routes and we don't want pedestrians to get intimidated. But the basic battle for space and separation from heavy flows of traffic seems to have been won.

Central London Grid

The Grid is the name given to the combination of Superhighways and Quietways in Central London. We have a map of the Grid, and we have the Superhighway plans so far as they go, and we have solid proposals for some of the Camden routes, but that seems about all. We have little indication of the standard that the boroughs other than Camden will apply to the Quietway routes. We have had one Quietway proposal from Southwark (QW2) in detail, and this has been criticised in detail elsewhere, with suggestions for how it could be better. It seems likely to fail LCC's criteria of vehicle flows below 2,000 PCU per day and speeds under 20mph with the design that has been proposed. It seems that the problem is political will from the borough to cut the minor-road rat-runs (like Tabard Street, which is parallel to the A2 and should not be a through-route), and it looks very likely that this kind of issue with the Grid Quietways will be repeated more widely unless Boris Johnson and his aides can somehow bring more persuasion to bear on these boroughs.

I've written about the inadequacy of many parts of the Grid plans before. The problem is basically one of the Mayor trying to promote changes on roads he doesn't control. One answer would have been for him to have included more TfL roads in the Grid. Kensington and Chelsea is most obviously not playing ball, and Westminster's commitments remains very vague, which is deeply worrying since, as can be seen, much the largest part of the Grid is in Westminster. The general lack of concrete plans by the boroughs for implementing the non-Superhighway elements of the Grid at the moment makes it look very likely that little of the Grid will have progressed beyond the paper stage by May 2016.

Quietways outside Central London

The Quietways beyond the Grid area are a separate funding stream for TfL, and this also is the only source of funds for new routes (or upgrades of old ones) for the boroughs that lack mini-Holland funding (that is, most of the outer boroughs). Sustrans was put in charge of doing the initial planning of these Quietways, and immediately there seemed to be divergences of opinion over what the scheme really was about. The emphasis in the Mayor's Vision for the Quietways was on 'low traffic back streets and other routes', but it also stated:

The planning for the Quietways, so far as it has got, seems to have been rather secretive, and LCC has only with difficulty managed to compile this plan, low-res version below, of roughly where the first routes are currently proposed to go.

It appears that this map shows the very most that will be achieved by May 2016. It will be seen that Andrew Gilligan's early concept of naming routes after tube lines that they follow has been abandoned, except for the Jubilee Line Quietway. This one seems a poor shadow of what he promised last year, when he spoke of a route from Central London to Wembley. Here is is shown stopping short of the North Circular, at Dollis Hill. The fact that there is a serious intention to extend it beyond the North Circular is indicated by an announcement of funding for a new cycling bridge over the A406 in Brent (and also another in Redbridge), but the timescale for these larger Quietway interventions seems to be beyond this mayoral term.

The Jubilee Line route, like CS11, depends at its southern end on the Royal Parks and Westminster agreeing to the closure of Regents Park to through-traffic. Through Camden the route, oddly, is only one or two blocks away from CS11, and then it follows an old LCN route in Brent, which requires more mode-filters and reversal of priority at junctions with other minor roads if it is to be made much more attractive than it is now. There's no guarantee of local councillors agreeing to measures like this, and little the Mayor can do to make them. So the worry is about standards. It's all very well to draw these lines on maps, but if the routes are fiddly to use, and traffic levels remain as they are at the moment, and on many roads, such as Maygrove Road and Chapter Road on the Jubilee route, cyclists just get squashed into tightly-parked narrow corridors with cars trying to get past them, then the Superhighways will prove far more attractive to all cyclists, of whatever level of experience, than the Quietways, which were supposed to be the routes 'particularly suited to new cyclists'.

Perhaps the most serious problem for the inner Jubilee Line route occurs where it meets West End Lane, West Hampstead, which it has to follow for a short while to connect between side-streets, because there is no other way to cross three railways. Traffic on this road is far above a 'quietway' level, but there is also no space for segregated lanes, and no realistic political prospect of closing this quite important local through-route to motor vehicles. Sustrans' proposal for this location has been a fanciful 'shared space' repaving, rejected by Camden Cyclists, rightly, as quite beside the point. This situation points to a fairly deep conceptual problem with the Quietways. Andrew Gilligan wrote in the Mayor's Vision that the Quietways would exploit London's 'matchless network of side streets, greenways and parks'. Where are the links in this network, exactly, and how should conflict be resolved at places like West End Lane?

Again, the most advanced of the Quietway plans seems to be CS2 in Southwark and Greenwich, which Gilligan has indicated will be delivered by 2016 subject to planning permission for a new path along the railway past Millwall Football ground. Bits like this could prove to be good and could justify the name 'Quietway", but examination of the map above will show that, in general, Sustrans have not succeeded in identifying the apocryphal 'matchless network of side streets, greenways and parks', because, of course, it is not a continuous network, and could never be made into one within the constraints of the funding offered, not to mention the realities of local politics. The concept is not entirely without merit: it is not that different to the orbital Green Routes plan of Copenhagen that I covered in my blogpost on that city. The political climate there, however, is sufficiently different, through cycle culture being sufficiently established, that the complete removal of traffic, parked and moving, from minor streets, and their conversion to genuinely green pathways does really occur. It is hard to see that happening immediately in many places in the London suburbs.

On a pessimistic assessment, it looks like the Quietways could become just a third attempt at the London Cycle Network (following Ken Livingstone's failed LCN+ project), on very similar routes: a byword for complex, inefficient, out-of-the-way routes that most cyclists will avoid and which will not significantly encourage cycling in Outer London, where encouragement is most desperately needed. What I would really have liked to have seen would have been a far better-funded equivalent of the Superhighways project specifically targeted on strategic main road sections in Outer London that would often be orbital, not radial routes. There are one or two projects coming from the boroughs that do approximate to this: there is currently a consultation out from Hounslow on possible cycle tracks on Boston Manor Road, the A3002, with proposals that look really rather good. I think this kind of thing, solving specific outer borough link problems, is likely to prove a more effective expenditure of funds than the very distributed low level of funding not achieving consistent high quality that is possibly emerging as the pattern for the Outer London Quietways.

Mini-Hollands

Three mini-Hollands were selected this spring: Enfield, Kingston and Waltham Forest. The following description is taken directly from the TfL site:

A reminder: the Vision is aiming for a doubling of cycling in London over 10 years, achieved mainly through these four programmes:

- Cycles Superhighways (Including the E-W "Bike Crossrail")

- The Central London Grid

- Quietways outside Central London

- Outer-London mini-Hollands

Now the first thing to say is that the rate of progress has been disappointing. Summer is the usual time for spades to be put in the ground for major work on the roads. I thought a year would be adequate for Transport for London to put their plans in place and assemble the correct staff, and that we would probably see something happening this summer. But summer passed, and nothing much happened, except a draft of the much-delayed, and in the event exceedingly lengthy and somewhat un-focused London Cycle Design Standards document was released for consultation. (See the excellent Cycling Embassy response on this.) The Cycling Commissioner, Andrew Gilligan, has been giving talks everywhere, and press releases have been common, but there's been no spades in the ground. What has been built in the last 18 months was either in train before (as was the Cycle Superhighway 2 extension), or the result purely of a borough initiative (as was the rebuild of the Royal College Street cycle track).

On the other hand, though it is getting going painfully slowly, there are signs of a seriousness to the project that go far beyond what we have been used to seeing before in the politics of UK cycle provision. I have, for example, actually watched (sad, benighted creature that I am) the examination of the chief officers of the project, including Gilligan and Lilli Matson, TfL's Head of Delivery Planning, by the GLA's Budget Monitoring Subcommittee. It is very clear if you watch this that we are in a rather different world to the borough Town Hall meetings of old where a 'Cycling Officer', a rather unimportant council employee who happened to be quite keen on cycling, would turn up before a few pretty uninterested councillors in a dirty yellow lycra suit and explain how he proposed to spend a few thousand pounds on painting some lines on pavements. Now, we have people establishing the serious business case for the expenditure, monitoring and auditing by actual outcome, of how many cycle journeys are generated, for hundreds of millions of pounds spent across a city of 10 million people. This is a hard-headed world which is little to do with wanting to 'look green' or create a bit of good PR with 'cyclists', but everything to do with keeping a major city moving and keeping it in business, and spending public money sensibly and effectively.

So what of the four programmes? In brief, if you haven't got time to read further, I'd say this: The Cycle Superhighways are now looking quite promising as the standards, programme and timetable for them is becoming clear. The timetable, nature and likely ultimate success of the Central London Grid is much less clear, and that is because TfL doesn't control most of it, the boroughs do. The programme for the Quietways is becoming slightly clearer, but the standard of implementation is in doubt. There seems to be a problem with people understanding the nature of the Quietways; Andrew Gilligan seems to have to keep explaining it again, and that must be his fault for not being clear enough from the start. The mini-Hollands still have not progressed sufficiently to draw any conclusions.

Superhighways

According to Gilligan at the budget subcommittee, around half of the total budget for Superhighways (£209m) is scheduled to have been spent by May 2016. The initial four superhighways that were created by painting the road blue – CS2 from Stratford to Aldgate, CS3 from Barking to Tower Gateway, CS7 from Merton to The City and CS8 from Wandsworth to Westminster are promised to be re-engineered 2016. However, the only one for which we have seen plans is the notorious CS2. These are being consulted on currently (ends 2 November), and look worth supporting, containing a large element of segregation, though the solution for Bow Roundabout is still sub-optimal, and a further round of improvements here is promised at a later date.

Then there are the two 'new' un-numbered Superhighways, known as the East-West (previously 'Bike Crossrail') from Tower Hill to Acton, and the North-South from Kings Cross to Elephant & Castle. These are due to be completed by May 2016, except for the Westway section of the East-West. They are being consulted on now (here and here). You should act quickly to respond, if you have not already done so: consultation closes 2 November. The plans have been well-received by campaigners and bloggers, being again for mostly segregated tracks achieving a generally high standard of provision and capacity. These new Superhighways also meet two of the main criticisms levelled at the original Superhighways plan: that the routes didn't go into the centre, and they didn't connect up. These two Superhighways will cross at Blackfriars north junction, though they will be at different levels there. They will be connected by a major junction remodelling, converting one of the current slip-roads off the bridge into the connecting two-way cycle track. Construction of all this will mark the final success of the Blackfriars campaign that this blog covered extensively in 2011.

|

| What LCC demanded in 2011 |

|

| What is now being offered. Sustained campaigning and protest by thousands of people put this on the table as a realistic possibility. |

There are still big gaps in the East-West plan, mostly concerned with the Royal Parks. What to do at St James's Park and in front of Buckingham Palace still has not been decided, though the suggestion of replacing the horse ride by Constitution Hill with a cycle track is a good one. Andy why, at the chaotic Wellington Arch, why do TfL propose 'a larger shared space to replace sections of grass to provide more space for pedestrians, cyclists and horses'? Why not just have clear dedicated routes so everybody knows where they are? Using the Carriage Drives in Hyde Park is a good plan, as they don't get disrupted by the park's frequent commercial entertainments, but these sections have not been designed yet. Different options are given in the Lancaster Gate area, and the idea for using the elevated A40 Westway to Acton seems still sketchy: further consultation on this is promised in 2015.

On the other hand, the plan for The Embankment, Bridge Street and Parliament Square is a clearly-defined game-changer: a high-capacity, high-profile two-way cycle track driven right past the Houses of Parliament and across the formerly intimidating and hostile gyratory of the Square. For this section alone the plans would deserve massive praise, and the scale and ambition of the East-West and North-South Superhighway concepts overall demand that all who are interested in the environment of the city and its transport network, whether they cycle or not, show their support.

Of the other Superhighways, CS5 Belgravia to New Cross is supposed to be finished by the end of 2015, and there may then be an extension east of New Cross. The plans for extensive segregation of the inner section, Belgravia to Oval, were consulted on this Summer, and look quite good. The outer section will use semi-segregation, we are told, but the exact character of this does not seem to have been decided.

CS1 City to Tottenham will not be on the roads originally planned, it will be on smaller roads, and possibly built by Autumn 2016. CS11 from Regents park to Brent Cross is also due to be finished by Autumn 2016. It depends on Westminster and the Royal Parks agreeing to the closure to through-traffic of the Outer Circle. It will thence run up Avenue Road, Finchley Road and Hendon Way, but we have see no plans for this so far.

CS4 Tower Bridge to Woolwich is supposed to be finished by 2017, and a new (so far un-numbered) Superhighway is planned on Lea Bridge Road in connection with the Waltham Forest mini-Holland project. CS9 which should have gone from Hyde Park to Hounslow has run into opposition from the Royal Borough of Kensington and Chelsea. It looks like TfL will only be able to progress the sections in Hammersmith & Fulham and Hounslow, and the timetable for these is currently unclear.

CS4 Tower Bridge to Woolwich is supposed to be finished by 2017, and a new (so far un-numbered) Superhighway is planned on Lea Bridge Road in connection with the Waltham Forest mini-Holland project. CS9 which should have gone from Hyde Park to Hounslow has run into opposition from the Royal Borough of Kensington and Chelsea. It looks like TfL will only be able to progress the sections in Hammersmith & Fulham and Hounslow, and the timetable for these is currently unclear.

That's a total of twelve Superhighways, the number originally projected, though they are not all in the originally projected locations. The original CS12 Angel to Muswell Hill and CS10 Hyde Park to Park Royal have been abandoned. CS10 is supposedly replaced by the East-West route on the A40, but this means, with the original CS11 alignment having been moved east, from the A5 to the A41, that Brent, quite an inner borough (though technically an Outer London one) will have been completely left out of the Superhighways programme.

I have to say I take all TfL's projected completion dates with a massive bag of salt. We were told, after all, in late 2012, that CS5, 9, 11 and 12 would be launched in 2013. Well, clearly the rethink on the whole nature of the CSHs after LCC's Go Dutch Campaign and the appointment of Gilligan as Commissioner caused that three-year delay. But the longer timescale is for the best if what we get is actually good. The designs we are seeing now show a step-change in quality from what we were offered before. Problems tend to come at a few places at big junctions where there is slightly too much emphasis on mixing and sharing with pedestrians: we need separation and clarity to allow flows of both cyclists and pedestrians to continue to grow and co-exist in harmony. We need efficient cycle routes and we don't want pedestrians to get intimidated. But the basic battle for space and separation from heavy flows of traffic seems to have been won.

Central London Grid

The Grid is the name given to the combination of Superhighways and Quietways in Central London. We have a map of the Grid, and we have the Superhighway plans so far as they go, and we have solid proposals for some of the Camden routes, but that seems about all. We have little indication of the standard that the boroughs other than Camden will apply to the Quietway routes. We have had one Quietway proposal from Southwark (QW2) in detail, and this has been criticised in detail elsewhere, with suggestions for how it could be better. It seems likely to fail LCC's criteria of vehicle flows below 2,000 PCU per day and speeds under 20mph with the design that has been proposed. It seems that the problem is political will from the borough to cut the minor-road rat-runs (like Tabard Street, which is parallel to the A2 and should not be a through-route), and it looks very likely that this kind of issue with the Grid Quietways will be repeated more widely unless Boris Johnson and his aides can somehow bring more persuasion to bear on these boroughs.

|

| Current Central London Grid plan |

Quietways outside Central London

The Quietways beyond the Grid area are a separate funding stream for TfL, and this also is the only source of funds for new routes (or upgrades of old ones) for the boroughs that lack mini-Holland funding (that is, most of the outer boroughs). Sustrans was put in charge of doing the initial planning of these Quietways, and immediately there seemed to be divergences of opinion over what the scheme really was about. The emphasis in the Mayor's Vision for the Quietways was on 'low traffic back streets and other routes', but it also stated:

Where directness demands the Quietway briefly join a main road, full segregation and direct crossing points will be provided, wherever possible, on that stretch.This was always going to be a prescription that was hard to apply in many places in Outer London, where 'low-traffic back routes' are not very available or useful, and therefore the joining of main roads might not be so 'brief'. I pointed out last year how the level of funding allocated to these routes did not suggest that many intractable problems that require heavy engineering solutions, such as the mess of railway and main road corridors that makes the centre of the Borough of Brent quite impenetrable by bike, could actually be solved within the limits of this programme. It soon became clear that Sustrans and some people in the boroughs were interpreting the Quietways as being necessarily, and thus limitingly, on quiet roads, and being necessarily low-intervention, which is, of course, what the name does suggest. However, Andrew Gilligan had repeatedly said that where no satisfactory back-street route exists on the desired alignment, Quietways can be on main roads, and they can be high-intervention, i.e., physically segregated. This raises an unanswered question of how bad the backstreet route has to be before the backstreet idea is abandoned. The other question which remains unanswered is the same as for the Grid: how prepared will local councillors be to actually cut the rat-runs to make back-street routes attractive?

We will use judicious capital investment to overcome barriers (such as railway lines) which are often currently only crossed by extremely busy main roads. Subject to funding, land and planning issues, we will build new cycling and pedestrian bridges across such barriers to link up Quietway side-street routes.

The planning for the Quietways, so far as it has got, seems to have been rather secretive, and LCC has only with difficulty managed to compile this plan, low-res version below, of roughly where the first routes are currently proposed to go.

It appears that this map shows the very most that will be achieved by May 2016. It will be seen that Andrew Gilligan's early concept of naming routes after tube lines that they follow has been abandoned, except for the Jubilee Line Quietway. This one seems a poor shadow of what he promised last year, when he spoke of a route from Central London to Wembley. Here is is shown stopping short of the North Circular, at Dollis Hill. The fact that there is a serious intention to extend it beyond the North Circular is indicated by an announcement of funding for a new cycling bridge over the A406 in Brent (and also another in Redbridge), but the timescale for these larger Quietway interventions seems to be beyond this mayoral term.

The Jubilee Line route, like CS11, depends at its southern end on the Royal Parks and Westminster agreeing to the closure of Regents Park to through-traffic. Through Camden the route, oddly, is only one or two blocks away from CS11, and then it follows an old LCN route in Brent, which requires more mode-filters and reversal of priority at junctions with other minor roads if it is to be made much more attractive than it is now. There's no guarantee of local councillors agreeing to measures like this, and little the Mayor can do to make them. So the worry is about standards. It's all very well to draw these lines on maps, but if the routes are fiddly to use, and traffic levels remain as they are at the moment, and on many roads, such as Maygrove Road and Chapter Road on the Jubilee route, cyclists just get squashed into tightly-parked narrow corridors with cars trying to get past them, then the Superhighways will prove far more attractive to all cyclists, of whatever level of experience, than the Quietways, which were supposed to be the routes 'particularly suited to new cyclists'.

|

| Chapter Road, Brent, as it is at the moment, part of the the proposed Jubilee Line Quietway. |

Again, the most advanced of the Quietway plans seems to be CS2 in Southwark and Greenwich, which Gilligan has indicated will be delivered by 2016 subject to planning permission for a new path along the railway past Millwall Football ground. Bits like this could prove to be good and could justify the name 'Quietway", but examination of the map above will show that, in general, Sustrans have not succeeded in identifying the apocryphal 'matchless network of side streets, greenways and parks', because, of course, it is not a continuous network, and could never be made into one within the constraints of the funding offered, not to mention the realities of local politics. The concept is not entirely without merit: it is not that different to the orbital Green Routes plan of Copenhagen that I covered in my blogpost on that city. The political climate there, however, is sufficiently different, through cycle culture being sufficiently established, that the complete removal of traffic, parked and moving, from minor streets, and their conversion to genuinely green pathways does really occur. It is hard to see that happening immediately in many places in the London suburbs.

On a pessimistic assessment, it looks like the Quietways could become just a third attempt at the London Cycle Network (following Ken Livingstone's failed LCN+ project), on very similar routes: a byword for complex, inefficient, out-of-the-way routes that most cyclists will avoid and which will not significantly encourage cycling in Outer London, where encouragement is most desperately needed. What I would really have liked to have seen would have been a far better-funded equivalent of the Superhighways project specifically targeted on strategic main road sections in Outer London that would often be orbital, not radial routes. There are one or two projects coming from the boroughs that do approximate to this: there is currently a consultation out from Hounslow on possible cycle tracks on Boston Manor Road, the A3002, with proposals that look really rather good. I think this kind of thing, solving specific outer borough link problems, is likely to prove a more effective expenditure of funds than the very distributed low level of funding not achieving consistent high quality that is possibly emerging as the pattern for the Outer London Quietways.

Mini-Hollands

Three mini-Hollands were selected this spring: Enfield, Kingston and Waltham Forest. The following description is taken directly from the TfL site:

Kingston

A major cycle hub will be created and the plaza outside Kingston station will be transformed. New high-quality cycling routes will be introduced together with a Thames Riverside Boardway - a landmark project which could see a new cycle boardwalk delivered on the banks of the river.

Enfield

The town centre will be completely redesigned with segregated superhighways linking destinations, three cycle hubs delivered across the Borough and new greenway routes introduced.

Waltham ForestThese are funded to the tune of £30 million each. The Enfield project seems to have proved most locally controversial, with shopkeepers mobilising against it, and the Enfield Cyclists organising a counter-campaign of demonstratively spending money in shops to try to prove the power of the 'pedal pound'.

A semi-segregated Superhighway route along Lea BridEnfge Road will be developed as well as a range of measures focused on improving cycling in residential areas and creating cycle friendly, low-traffic neighbourhoods.

The most actual action so far has been seen in Walthamstow, where a series of temporary experimental road closures were put in and then taken out again. This is like the '20 bollards' game, where you have only twenty bollards to distribute around your town, and you need to position them to most effectively reduce rat-running traffic to create useful new cycling and walking routes and enhance local life. Again, reaction has been mixed, but there seems a lot of positivity around the Waltham Forest mini-Holland, and campaigners seem to think it has a good chance of being accepted by the community, and forming a good template for other Outer London town centres in the longer term. But broadly, because the selection process took so long, not enough has actually happened in the mini-Hollands yet to write much about them.

The selection procedure itself, the holding of the competition, was I think one of Andrew Gilligan's aims, successfully completed. It did get some previously pretty cycle agnostic, or even hostile, local authorities to start seriously thinking about radical change to kick-start more cycling in Outer London, lured by the cash promise, and the fact that the subject seemed to be suddenly in fashion, and that this was the project of a Tory mayor, potentially outflanking the Left on a 'green' issue. It remains to be seen whether anything from these unsuccessful mini-Holland bid plans will see the light of day; Gilligan has promised in letters to the boroughs that some projects will be pursued, and has budgeted for a number of mini-Holland 'consolation prizes' to finance the best ideas that came out of the competition in the non-winning boroughs, including the two new bridges across the North Circular I have already mentioned. Implementation of these however seems to be beyond 2016.

Conclusion

How to summarise? It has been difficult writing this post. I have started several times, and had to rewrite because of new developments and announcements. The Mayor's project is now gathering pace. A couple of months ago I would have made a much more negative, perhaps slightly bitter, assessment of where it had got to, compared to the promises of the Vision document. But now we have seen more of the new Superhighway designs, we can see that our campaigning over the last four years or so has been a success: it has produced a mind-shift in the ambitions of the people tasked with designing cycle facilities in London. The mind-shift of course has not spread to many local politicians, who have direct control over most of our roads, and therein lies the rub. There is plenty more campaigning that needs to be done, in fact, there will never be an end to it, as David Hembrow points out from the example of the apparently miraculous Netherlands. LCC had exactly the right idea with its Space for Cycling Campaign for the local elections: taking very specific demands for each ward right to each local ward councillor and candidate. This did have an effect, rather like the mini-Holland competition process, of making a few more people think properly about the issues, or at least start listening to the arguments, for the first time, though I don't expect miraculous results from it of all the ward 'asks' actually being delivered in the next few years. It was a stage in a process.

London's cycling revolution will certainly spread from the centre outwards, and the Superhighways will carry it to the suburbs. In the foreseeable future it will remain quite limited, though. The target of 5% mode share by 2025 might well be achieved, but this would still leave most Londoners out from the benefits that cycling can provide, which is rather sad, and it will also limit the success of the city overall. We've see a tremendous reaction from business leaders to the Superhighway proposals, and it's been found that a vast majority of ordinary Londoners support them as well. I always expected this kind of reaction to visionary, transformative proposals for our streets; I have said repeatedly in this blog that this is what would happen if you put to people a striking, coherent vision for change. I said this was why we in the cycling world should stop messing around asking for scraps that nobody really could see the point of, and should start to think far bigger, about what a real cycling and linked quality of life revolution would look like in London. There is now a growing realisation that London needs to compete with other world cities in terms of the quality of life it offers to a highly mobile skilled workforce. Competing on salaries or low levels or either personal or corporation tax is not enough. It is this economic driver that is increasingly recognised, and will increasingly be recognised, as the impetus for change.

This should encourage Boris Johnson and his aides and officials to become even more bold in laying down the infrastructural basis for the cycling revolution before he leaves office. We need all the other Superhighway plans quickly, and we need top quality maintained at the difficult places with many competing demands. We need better control and more up-front leadership over the Central London Grid and the Outer London Quietways to prevent any money being wasted on cosmetic projects which fall short of the best standards. We need the Royal Parks Agency, the Corporation of London, the City of Westminster and Royal Borough of Kensington and Chelsea to come unambiguously on board and we need to find ways to put pressure on the from every angle, from residents, businesses and commuters, to do so. We need flexibility over the definitions of the various projects, so it is clear to all that we can have segregated tracks funded on long stretches of main road in Outer London, and this in fact becomes a thing that is expected. We need the major essential linking infrastructural elements such as the new North Circular crossings delivered more quickly. We need more funding for Outer London and plans for a second round of mini-Hollands after 2016 to start to develop a real usable cycling grid outside the centre. Finally, the Mayor and GLA need to get a grip on miscellaneous 'third-party' development projects, such as, in my part of London, Brent cross Cricklewood, and Old Oak Common, and ensure that everything built in them meets the Cycling Level of Service in the London Cycle Design Standards. There should be no question of more major road junctions being rebuilt in London without high-quality cycle provision.

There is progress, but the gap between London and the best places for cycling in world continues to grow. We continue to lose further generations of children to cycling. We continue to see illegal levels of pollution in our city, and massive levels of pollution-related disease. We need to be sober. Cycling appears quite popular at certain places and certain times in London, but we're really still in the remedial class of world cities for cycling. Cycling still hasn't made the breakthrough to become the obvious method for most people to consider for short, routine journeys. Our roads still feel, and, are, far too dangerous. We need to continue to demand far more. We can't let up.

Sunday, 19 October 2014

While focus is on the Mayor's Superhighways, Camden plans to double its length of segregated track

I wrote a post about two years ago entitled While Boris so far fails to 'Go Dutch', Camden quietly gets on with it. This is something of a 'second round' of that. Today, there is somewhat more sign of Boris Johnson trying to make a permanent mark on London before his mayoral term ends in May 2016 by building some good-quality cycle routes. Though what he will have achieved still looks likely to fall well short of the commitments he made before the 2012 election in response to London Cycling Campaign's Love London, Go Dutch campaign, in particular, he will not have completed the Cycle Superhighway programme to an adequate 'Dutch' standard on all its routes (nowhere near, in fact), the plans for the East-West and North-South superhighways are a substantial advance and have generally been welcomed by campaigners, business, the public and the media, while plans for Cycle Superhighway 5 in south-west London and the long-demanded upgrade to Cycle Superhighway 2 in east London look pretty good as well.

I'm planning to make a more general assessment of where the Mayor's Cycling Vision has got to, 18 months after it was announced, in another post, although attempts to write that keep getting overtaken by relevant events. However, I will to draw your attention here to the fact that, as coverage has been concentrated on the plans above, the Borough of Camden, pioneers of the on-street segregated or semi-segregated cycle track in London, have been continuing to 'get on with it' in a manner that, though it is not above criticism, must be said is not being replicated by any other borough.

When the rebuild of the Royal College Street cycle track was announced in 2012, replacing the two-way track on one side of the street, which had had an intractable collision problem at two junctions, with two one-way tracks, I supported the scheme because it was linked to a commitment to extend the track northwards to Kentish Town Road, making it go from 'somewhere to somewhere', to adapt the words of Jon Snow when he opened the track in 2000. Since then, this has developed into a plan to extend the route southwards as well, down Pancras Road and Midland road, forming a more main road and direct alternative route to the Kings Cross area than the existing back-strteet Somers Town Route (one of the oldest cycle routes in London, dating from Ken Livingstone's GLC era, before 1986).

The consultation on the northern extension closed earlier this month, and the response from Camden Cycling Campaign can be seen here. The gist of the scheme is that Royal College street will become two-way for bikes all the way, the bike space generally protected by rubber armadillos, and in places by car parking on the east side as well. The cycle tracks bypass bus stops and loading bays on the inside. The southbound approach to the Camden Road junction is not protected, and this is a concern, though the northbound is protected.

The southern extension to the route is now being consulted on. The consultation runs to 14 november, and I encourage people to respond. This will be an enormously important pice of infrastructure, linking residential areas in Camden with the big employment growth areas around Kings Cross and St Pancras, with the new Google headquarters, the Francis Crick Institute opening in 2015, and much else. Argent, the developers of Kings Cross Central, say that their site will eventually be home to some 30,000 office workers, 5,000 students and 7,000 residents. It looks as if, at last, we have some cycle route planning in London that is coming at exactly the right time. This route will link southwards into the existing east-west Seven Stations Link segregated cycle route across Bloomsbury (which itself needs major improvement of course, to cope with the high number of cyclists it already attracts), and that will link to the Mayor's North-South Superhighway at Clerkenwell. We will have the beginnings of a functioning, continuous segregated or semi-segregated network on the streets of central and north London.

It is of credit to officers at Camden that they are conceiving part of this Royal College Street route extension also as the beginning of an east-west route across Camden Town. Ultimately this should run along Crowndale Road to Oakley Square and Hampstead Road. It is not too much of a stretch to suggest that the stage after that should be the construction cycle tracks on Hampstead Road to connect with Tottenham Court Road. This is consistent with the overall Central London Cycle Grid plan.

The overall network is being developed in stages, and the current consultation goes down south to the Pancras Road / Midland road junction (the tunnel under the railway lines). This junction was consulted on in August, along with a plan for a 2m wide kerb-segregated cycle track on Midland Road northbound (in the contraflow direction), from Brill Place. This plan showed southbound cycling on Midland Road with taxis segregated to the left (there are lots of these serving St Pancras) but only a painted advisory cycle lane separating cyclists from the general (heavy) traffic flow. The Camden Cycling Campaign response called rightly for this design to be improved.

The plans for Pancras Road, currently being consulted on, are for armadillo-separated lanes on both sides, which will be 2m wide for most of their length (actually 2.5m wide for 105m, 2m wide for 375m, 1.5–2m wide for 34m, and 1.5m wide for 30m). There is no parking on this stretch, but there will be bypasses for the bus stops.