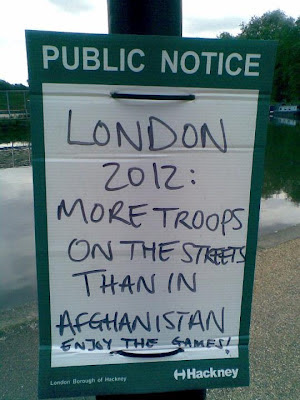

In modern usage, the phrase is taken to describe a populace that no longer values civic virtues and the public life.And if the bread becomes more meagre, then of course the circuses become more important. So as it is announced today that disposable income of UK citizens, on average, is at its lowest now since 2003 (quite an indictment of the economic performance of the country under two contrasting governments), the fact is somewhat lost in the razzmatazz around that greatest circus of all taking place in East London and elsewhere. Everybody feels so great about that, don't they? They more or less have to, don't they? Nobody really was allowed not to like the Danny Boyle spectacular, you were putting yourself in the company of a rather weird right-wing Tory and pretty much no-one else if you did not.

But while Britain's turbulent history of activism and political dissent was being celebrated in the ceremony and on TV, while the Suffragettes, who got arrested and mistreated for their fight for equality were remembered, strangely enough, right outside the Olympic arena, the great circus, people fighting for a equality and fair treatment in a different field were being arrested and mistreated by the police, pepper-sprayed and kettled. If a novelist imagining a dystopic sci-fi future Britain had composed the scene, he would have been doing a pretty good job.

It was probably inevitable that the Critical Mass bike ride on the night of the opening of the Games would end in trouble. Not because those involved wanted trouble; far from it, but because there was simply "no room" on the streets of Olympic London, both in a physical and a spiritual sense, for an event like this on that night. The police could not let it it happen. They could not allow the possibility of an area of streets close to the Olympic Park being gridlocked at that time. On any other occasion, yes, they could grudgingly live with it, but not on this occasion.

Yet Critical Mass is not a beast which can be controlled, for it has no organisation, no plan and no leader. It is merely a tradition, the kind of tradition which might otherwise have been celebrated in a show like Boyle's opening ceremony: a tradition of gathering of people on bikes at a particular time, the evening of the last Friday of the month, in a particular place, on the South Bank of the Thames, for a particular purpose, a meander round streets on a route determined on a whim by those at the front of the group, the objective being to fill the streets with a slow-moving cavalcade of bicycles in which riders feel safe and freed, for the moment, from the otherwise ever-present threat of dangerous interaction with motor vehicles: a critical mass of bikes.

It has often been said in the last few days that Critical Mass in not a protest, it is just a ride or an event, but in fact it shares characteristics of both protest and festival. It exists because the normal conditions for cycling on the streets of London (and other cities around the world where Critical Masses take place) are no good at all. There is no right enforced for cyclists to proceed safely, with fair and civilised treatment, on our roads as they stand. Critical Mass is definitely a kind of protest against, and a reaction to, that fact. It is a protest demanding a different order in transport and street hierarchy as much as the Suffereagettes were a protest demanding a different hierarchy in sexual politics. There is no Critical Mass in the Netherlands, where cycling is treated as a first-class form of transport, prioritised equitably with other modes.

The police tried to ban Critical Mass from the north side of the Thames, and they tried to prevent it from invading the sacred space of the Olympic Lanes, both of which conditions were inconsistent with the freeform nature of the event. There was a fundamental discordancy between the spirit of Critical Mass and the nature of Olympic Lockdown London. Eventually, after considerable unpleasantness, the police broke up the mass and herded the rump of it into a small street in Bow, where the participants were kettled, and in the end 182 of them were arrested and taken away in buses. Of this 182, only three have been charged with offences. The experience of one of those not charged, but held overnight in a cell, has been written up on opendemocracy.net. It makes a salutary read. You have to keep reminding yourself that the place where all this took place was not Burma, but London.

I have no relationship with Critical Mass. I have been on it, twice I think in two decades, in order to find out what goes on, and I am neither a fan of it not a detractor. I seek to understand. As with the suffragette movement, it seems to me there is a clear way for the government to deal with the recurring problem that Critical Mass poses, and that is to understand what the problem is that it is a reaction to, and to address that problem, by starting to correct the lack of resources and rights, the fundamental power imbalance, between those who choose to use the streets using their legs and using human-powered machinery, and those who choose to use them in motor vehicles.

It's not a thing that will be achieved in one legislative stroke, as was possible with Votes for Women. It will be a policy process. It has not started yet. Until it does, our cities will have to accommodate events like Critical Mass. There is a third alternative, which is that the right to peaceful protest on the streets will be stamped out in the UK. We seem to have gone a long way down that road already.

A police statement said:

People have a right to protest and it is an incredibly important part of our democracy … What people do not have the right to do is to hold a protest that stops other people from exercising their own rights to go about their business – that means athletes who have trained for years for their chance in a lifetime to compete, millions of ticketholders from seeing the world's greatest sporting event, and everyone else in London who wants to get around.That of course is an argument that could effectively be used to end all street protest, at any time. A right is not a right if it can be taken away whenever it has inconvenient consequences for some people. It is a method of oppression to try to forcibly prevent protest rather than listening to what the protesters want and adjusting policy accordingly, which would, if not bring an end to all such protests, reduce their support and nuisance value.

Like the Roman rulers criticised by Juvenal, the rulers of modern Britain seek to distract attention from the decayed and disfunctional states of both our democracy and our environment by giving us entertainment and spectacle, while shoring up the privileges of an elite. The Roman Empire did not fall for 300 years after Juvenal wrote of panem et circenses: it's a policy that can work, for the emperors at least, for a long time. It's a Big Mac and an Olympic ticket now – never mind that all the expediently-made promises about the green and socially-responsible Olympics were all broken and forgotten.

A state run in this way, is however, quite inefficient, and, as the declining disposable income of citizens attests, I expect a continuing slow economic decline for a UK that neither modernises its political culture and structures, nor embraces dissent and alternative views, nor tackles significant social inequalities, nor learns to live in harmony with the natural environment, nor allows safe space in its cities for children and old people and others on bikes.

There is a petition to sign demanding justice for the Critical Mass 182, and the campaign against the closure of the Lea towpath goes on. And there's a good outsiders' view of what is going on in London from, of all people, the Americans, on NBC News.